With

an endorsement of fascination in the process of interior innovations, radically

alter the way we are able to carry out simple daily tasks has driven me to

discuss whether the global issue of aesthetically pleasing buildings have a

major effect on achievement in classrooms or whether other factors such as,

engagement of staff, air quality, lighting, temperature and foreign sound have

a more significant influence.

Psychologists, Talton and Simpson (1987)

comment that ‘The classroom is the basic structural unit of our educational system’

[4], the nature of the classroom is clearly affected by the school design

and objectives adopted at the school level. There is reason to expect the environment

to affect behaviour: Maslow and Mintz (1956) found that participants in an

‘ugly’[4] room made significantly less positive judgements about

photographs than did the participants doing the same task in a ‘beautiful’ room

.However, it is difficult to generalise from these observations to identify

requirements for a school classroom. Maslow and Mintz’ findings were reliable

to an extent because the same procedure may be repeated in order to reconfirm

results.

In a pilot study by the University of Salford and

architects, Nightingale Associates, it was found that the ‘classroom

environment can affect a child’s academic progress over a year by as much as

25%’.[1] The year-long pilot study was carried out in seven Blackpool

LEA primary schools in 2014. Data was collected from’ 751 pupils’[1],

such as their performance level in math, reading and writing at the start and

end of an academic year. During this study the holistic classroom environment

was evaluated, taking into account different design parameters such as

classroom orientation, natural light and noise, temperature and air quality.

Other issues such as flexibility of space, storage facilities and organisation,

as well as use of colour were evaluated. Results communicate that, ‘Notably,

73% of the variation in pupil performance driven at the class level can be

explained by the building environment factors measured in this study’. [1]

This highlights the importance of focusing on the design and aesthetics in working

environments. Moreover, this may also apply to work places all around the world

alongside schools as demonstrated by the atmosphere at Google headquarters,

where employees are intentionally motivated by the aesthetics of the building

leading to an efficient and energized workforce. The pilot study was

commissioned by THiNK, the research and development team at Nightingale Associates

increasing the reliability of the study. The results have also been accepted in

an international peer reviewed journal: [P.S.Barrett, Y. Zhang, J. Moffat and

K.Kobbacy (2012). [3]

‘The

science of designing learning environments is currently remarkably

under-developed’, argued architect and CABE Commissioner Emeritus the late

Richard Feilden in 2004. [8] In a similar vein, Professor Stephen

Heppell argued at an expert seminar that ‘traditionally, we have designed for

productivity, processing large numbers of children through the effective use of

buildings, designing a room for learning is very complex... What is needed is a

new approach and new solutions for school design to reflect the changing needs

of learning in the 21st century’. [5] As Professor David Hopkins,

the Education Minister’s Chief Advisor on School Standards, argued at the same

seminar: ‘Schools today have the responsibility for personalised learning and

its design’. [7] Overall, the arguments put forward in supporting

aesthetics effecting achievement, primarily suggests that working environments

should be designed in ways which adapt and are suited for this day in age in

order to maintain engagement from students.

It

has been pointed out that school buildings and classroom layouts vary globally in

ways that are related to understandings and philosophies of education as well

as to material resources (Alexander, Culture

and Pedagogy:2000) [6] .From a study of 30 primary

schools in five countries, Alexander reports some interesting consistencies

such as the much more elaborate displays of children’s finished work in the

American and British schools (op.ci,p.184) [6] ; the arrangement of the children in

rows of individuals in India, rows of pairs in Russia and around work ‘centres’

in the USA (p.333-334) [6] ; and the contrast of ‘a great deal of

light’ in all the Russian classrooms with some British and American classrooms

requiring ‘artificial light throughout the day’. (p.185) [6].

However, research specifically concerned with the effect of the learning environment

on students are carried out in Western Europe and, particularly, in the USA.

The subjectivity behind the global issue of whether it’s the aesthetics of the

classroom impacting achievement or other factors such as light intensity and

noise disruption effecting the concentration and in turn efforts put into work

by pupils, differs across the globe due to the influence of cultures and

traditions.

Some may argue that other factors have a

more of a major effect on achievement than the aesthetics of a classroom. There

appears to be a strong link between effective engagement with staff, students and

the success of environmental change in having an impact on behaviour and

achievement all round. Teachers’ attitudes and behaviour are vitally important

to the use made of space. This challenges the idea of aesthetics being a major

impact on achievement due to the view on teaching morale being more important. PricewaterhouseCoopers

(2000) [9] consider staff morale to be of key importance while Berry

(2002) [9] found there were improvements in attitude among all users

after a school was physically improved. The idea of trying to affect the nature

of the school environment is referred to by a number of writers. Cooper,

himself architecturally trained, warns that ‘Those who offer guidance on the

planning of buildings tend to assume that there is some necessary relationship

between the design of a building and the behaviour of those who occupy it’

(1981, p.125) [9]. Furthermore, in regards to the involvement of

children in design is significant in overcoming the conservatism of many

adults. Thus, this suggests the involvement of students in designing a

classroom would result in an increase of engagement and achievement. However,

this may be unreliable evidence due to it depending on the students and their

mind-set towards their education individually.

There is consistent

evidence in regards to the effects of basic physical variables such as air

quality, temperature and noise on learning. Earthman (2004) [11]

rates temperature, heating and air quality as the most important individual

elements for student achievement. Two psychological studies (Young et al, 2003;

Buckley et al, 2004)[2] mention the importance of these issues in

reports addressing the needs of particular US states’ schools, while Fisher

(2001) [12] and Schneider

(2002) [2] similarly rate these factors as likely to affect student

behaviour and achievement. The studies offer some reasonably clear findings but

also some disagreement. Earlier work, in the USA, emphasised comfortable temperatures

and advocated an increased use of air-conditioning. There has been questioning

about maximum comfortable temperatures (Wong & Khoo, 2003)[13], relating

back to which factors have a major impact on achievement in classrooms to be an

international strive that may require dissimilar solutions and responses for

different countries.

|

| [This

photograph is taken from The Open Plan school (IDEA, 1970), perhaps indicative

of the difficulties of open-plan education where ‘classes shared little beyond

the vast open area and high noise level’. (Rivlin & Wolfe, 1985, p.177.)][10] |

Furthermore, it is prominent that air

conditioning, ventilation and heating systems are found to contribute quite

distinctly to the level of classroom noise (Shield & Dockrell, 2004)[14]

which would have an automatic effect on the concentration of students and thus

achievement. The importance of ventilation in educational establishments

continues to be emphasised (Kimmel et al, 2000[15]; Khattar et al,

2003[16]), while the inadequacies of indoor air in schools continue

to be reported (Lee & Chang, 2000[17]; Kimmel et al, 2000[15];

Khattar et al, 2003[16]) and linked to ill-health (Ahman et al, 2000)[18]

which would result in students being unable to participate in studies at

all. It is evident that the demands of clean air might come in to conflict with

the teacher’s desire to provide a comfortable, cozy and welcoming classroom,

resulting in designers being pressured to prioritise factors other than

aesthetics to please the main users of the classroom (the students).

It is extremely

difficult to come to firm conclusions about the impact of learning environments

because of the multi-faceted nature of environments themselves. Cultural and geographical

differences also highlight the importance of sensitivity to context. For these

reasons it is very difficult to make judgements about which areas are ‘worth’

focussing on in order to maximize achievements of pupils. There is clear

evidence that extremes of environmental elements (for example, poor ventilation

or excessive noise) have negative effects on students and teachers and that

improving these elements has significant benefits. My evaluation suggests that

the aesthesis in working environments in this case, classrooms do have a major

impact on achievement along with other factors; specifically engagement between

pupils and their teachers. I believe to involve the users of the classroom in

the process of design is an efficient way of building a healthy attachment

between students and their working environment which would motivate students to

achieve to their maximum potential. Personally, from my secondary school

experience at Loxford School of Science & Technology, I was able to

identify the impact of an aesthetically pleasing building and specifically

classrooms on students’ behaviour, conduct and achievement. A new and adapted

environment enhances the idea of a new beginning for many pupils encouraging

them to strive for success.

[The photograph [19] above shows Loxford School’s old building (in 2006). The aesthetics of the building has been significantly changed since 2010, indicated by the photograph [19] below.Along with the aesthetics of the classrooms and leisure areas being modified, uniform pupils’ attitude and staff morale was also targeted in order to impact achievement. The new building signifies the transgression for a new start allowing students to feel part of a new era.]

Research Essay; Bibliography:

1. University of Salford in Manchester `Study proves

classroom design really does matter’ (November 2012)

2.

J Buckley, M Schneider and Y Shang, LAUSD

School Facilities and Academic Performance. (25.8.04.)

[P.S.Barrett, Y. Zhang, J. Moffat and K.Kobbacy (2012)

4.

Christopher

B. Smith, M.ED., Avon-Maitland District School Board,

Ontario, Canada

Anthony N. Ezeife, Ph.D., Professor

of Math/Science Education Faculty of Education University of Windsor, Ontario,

Canada.

Talton

and Simpson (1987) & Maslow and Mintz (1956)

5.

CABE/RIBA, 21st Century Schools: Learning environments of

the future, (7.9.2004)

6.

Alexander, R. (2000) Culture

and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in primary Education (USA, UK,

Australia, Blackwell Publishing).

7.

Professor David Hopkins, ALAT’s Director of Education (February

5, 2015) ALAT

8.

Richard Feilden, Architect and CABE Commissioner Emeritus (2004).

9.

I Cooper, The Politics of Education and Architectural

Design: The instructive example of British primary education, British

Educational Research Journal, (1981: pg, 125).

10.

L G Rivlin and M

Wolfe, Institutional Settings in Children's Lives, Wiley, (1985).

11.

G I Earthman, Prioritization of 31 Criteria for School

Building Adequacy, (2004).

12.

K Fisher, Building Better Outcomes: The impact of school

infrastructure on student outcomes and behaviour, Department of Education,

Training and Youth Affairs (Australia), (2001).

13.

N H Wong and S S Khoo, Thermal Comfort in Classrooms in the

Tropics, Energy and Buildings, (2003).

14.

B Shield and J Dockrell, External and Internal Noise

Surveys of London Primary Schools, Journal of the Acoustical Society of

America, (2004).

15.

R Kimmel, Pupils' and Teachers' Health Disorders after

Renovation of Classrooms in a Primary School, Gesundheitswesen, (2000).

16.

M Khattar, Cool & Dry - Dual-path approach for a

Florida school, Ashrae Journal, (2003).

17.

S Lee and M Chang, Indoor and Outdoor Air Quality

Investigation at Schools in Hong Kong. Chemosphere, (2000).

18.

M Ahman, Improved Health After Intervention in a School

with Moisture Problems, Indoor Air, (2000).

19.

Loxford School of

Science & Technology. Photographs of the building in (2006 & 2010)

From several years of experience in being a young carer for my little brother who was diagnosed with mild autism at the age of 5, i developed a fascination in the way autistic children interact and communicate with the world. From further research on the psychology of colours and from day to day observations of ways certain aspects of design help to break down language barriers and alter concentration levels, i was eager to look into designing for the autistic.

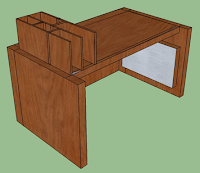

From several years of experience in being a young carer for my little brother who was diagnosed with mild autism at the age of 5, i developed a fascination in the way autistic children interact and communicate with the world. From further research on the psychology of colours and from day to day observations of ways certain aspects of design help to break down language barriers and alter concentration levels, i was eager to look into designing for the autistic. There seems to be a gap in the market in terms of products that adapt to the needs of autistic children in order for them to concentrate and focus outside of school. Specifically from domestic aspects, there isn't a variety of help out there for parents to encourage bonding or even continuing studies outside of the school environment. This could possibly be due to the routined nature of autistic children. However, surely a specification could be met to please both the child and guardian.

There seems to be a gap in the market in terms of products that adapt to the needs of autistic children in order for them to concentrate and focus outside of school. Specifically from domestic aspects, there isn't a variety of help out there for parents to encourage bonding or even continuing studies outside of the school environment. This could possibly be due to the routined nature of autistic children. However, surely a specification could be met to please both the child and guardian.